POW in Russia, page 3. Russian Gulags and Stalags S-Z

Primary investigator: Alan Newark braveheart562002@yahoo.com

Samara 1/26/05 I am trying to find records of Germans from Poland that were held at Russian DP camp at Samara, Russia following WWll. Thank You, Ron Covey rcmilret@charter.net

Sologubovka

SOLOGUBOVKA, Russia (Reuters) - Hundreds of German and Russian war veterans flocked

to this remote village on Saturday for the opening of Russia's largest war

cemetery, which is set to house the remains of up to 80,000 German soldiers.... The Russia Journal

Solovki THE DUTIFUL AND THE DAMNED: STALIN AND HIS MURDERS,

Lena Stuyrcevich. Teacher from the Ukraine. 1929 sent to Solovki. 1930 shot. Solovki basics.

By Harriet Crawley The Telegraph, London, UK Sunday, March 2, 20003

"Most of the gulag buildings have gone (Likhachev went back in 1966 and already they had disappeared) but there's still the trapeznaya, the dining hall which, he says, was crammed with not hundreds but thousands of prisoners sleeping on the floor, in lice-ridden filth, with no heating. Now it's empty, whitewashed; the cool lines of a vaulted ceiling have a defiant elegance.

"Finally we get to where I want to be: the gulag museum; it's housed near a monk's dormitory and the laundry. There are hundreds of photographs of inmates with the barest of information: name, profession and date of death (almost always "shot"). Now and then a relation has placed a flower beneath the photograph.

"It was Lenin who turned Solovki into a prison camp in 1922 for "undesirables" - political opponents such as mensheviks and socialist revolutionaries, as well as Jews, gipsies and ethnic minorities. "But it was Stalin who gave Solovki the status of gulag, filling it with kulaks, peasants and the intelligentsia of post-revolutionary Russia. The brightest and the best were sent to Solovki - scientists, engineers, teachers, writers, painters and poets. All summer typhus raged in the mosquito-infested swamps where the prisoners cut logs and peat; all winter, when the sea froze solid, half-starving men and women battled against blizzards in temperatures of -50c.

"'Strashna [ghastly],' Galia murmurs periodically as we look at photographs of the victims; below the alert sensitive faces their fate is typewritten: Lena Stuyrcevich. Teacher from the Ukraine. 1929 sent to Solovki. 1930 shot.

"I couldn't help noticing the photographs of Likhachev's camp commander, the proud Degtyarev who rode about on a white horse and was followed everywhere by a dog called Black that sniffed out runaways and barked enthusiastically when the executions started. In the 1930s it was Degtyarev's turn to be arrested and shot.

"Outside the church we have a magnificent view over the forest and a distant sea. Andrei points to the wooden steps.'That used to be a wooden chute for logs. When a prisoner could no longer work he was tied to a log and pushed down the chute.'",

4/2/07

Here is the information about most terrible Russian camp SLON/STO Solovki http://www.solovki.ca,

Russian huge site about Solovki Camp is here http://www.solovki.ca

Best regards, Yuri, email: info@solovki.ca

Solovetsky Islands Ukraine Report 2003, NO. 80: Article 11

VICTIMS OF POLITICAL REPRESSION REMEMBERED ON SOLOVETSKY ISLANDS, SITE OF FIRST SOVIET LABOR CAMP

MOSCOW, August 5. A commemorative festival entitled Days of the Politically Repressed will be held on the Solovetsky islands from August 6-9, marking the 80th anniversary since the labour camps were opened here. As a Rosbalt correspondent was informed by the press office of the Moscow administration today, the festival is being organised this year by the Solovetsky nature reserve, the Memorial centre of Saint Petersburg, the international Memorial organisation in Moscow and also the Moscow administration.

The first labour camp was opened on the Solovetsky islands in 1923. A whole network of such camps were later set up by the NKVD, which Russian writer Alexander Solzhenitsyn later termed as the GULAG Achipelago. The idea to hold a commemorative festival to remember the victims of political repression arose in 1998 and several former prisoners and their relatives were invited to the event as well as leading human rights' activists, historians and journalists.

More than 100 guests from Russia and Ukraine are expected to attend this year [2003]. They will visit the Solovetsky Kremlin and the Church of the Ascension which was used as an intimidating isolation cell during the days of Stalin.

Also, a new exhibition will open on August 6 in the Solovetsky Museum containing the names of all the former prisoners who were shot on the islands. ( UKRAINE REPORT is sent FREE of charge; e-mail to Morgan Williams, morganw@patriot.net.)

Stalag IIC Searching for Ukraine POWS in Stalag IIC:

Hello,

I'm searching for information about Soviet POWS in Stalag IIC, Greifswald. Looking

for information about the Wolgast-Peenemunde branch of the main Stalag in Greifswald.

POWs there worked on the V2 rocket site at Peenemunde. Any help would be appreciated.

Linda Hunt docufind@earthlink.net

Temwod, Mykolayiv, Ukraine

Hello Olga

would you know where i can find some information about a certain pow camp that

imprisoned german soldiers in the vicinity of temwod(sp?) mykolayiv, ukraine...i

just found out that it is there that my grandfather died and i might have

a chance to visit this region in july of this year...of course i would love

to find out more, especially the regiment these camps had...for example,

it was explained to me that the identification was removed from the prisoners

at the time of entrance to the camp and that once they had died their names

went into a record in alphabetical order...it would interest me what might

have become of his EM-identification and his body...did they just throw them

away????? thanking you in advance, christina wegner christinawegner@hotmail.com

Truruolya (or something like this) TB camp

Apr 16, 2018 Hello Olga,

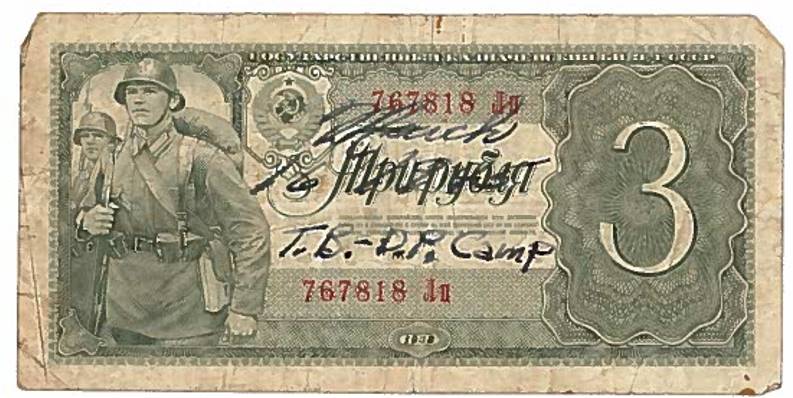

I found your website on displaced persons camps. I have a Russian bill with T.B. – D.P. Camp written on it. I have not been able to determine what camp T.B. is or where it is (assume it was in Russia). Would you be able to help? The date on the bill is March 16 1945. Mark.Bracken@andritz.com

Review by Alan Newark:

I have firstly looked at sites ref Carpathian camps because, I could be wrong, the helmets and uniforms of the soldiers on the bill suggest that they are Romanian = as seen in photos of Romanian troops around Sevastopol & Stalingrad.

As for when the bill was printed, there are two clues suggesting that it was issued after the Red Army & the Communist Party occupied & took political control of Romania:

(i) in the top right hand corner of the bill are, faintly discernible. the Cyrillic letters CCCP i.e. USSR..I am tempted to think that the words across the top of the bill could, paraphraised, be Romanian Soviet Socialist Republic USSR?

I don't have a powerful enough magnifier & am open to suggestions

(ii) also visible but miniscule is a typical SSR - style republic flag /banner with, in the centre, a 5-pointed red star.

As noted, I have run some broad sweep Carpathian region searches and will carry on with these.

Meantime, there is one possible explanation for the letters..T.B...and that is..Tuberculosis. I ran some basic checks & the above appeared.

Thinking on different levels...I have also noted the bill's bank / issuer number & will ask my spies to snoop around.

Meantime, a cocktail of patience, perseverance and thinking outside the box is a potent tool.

Here's to a successful end result.

Best regards...Scottish All :-) braveheart562002@yahoo.com

Vorkuta, Norilsk and Kolyma: Which camp was the worst? Gulag: A History of the Soviet Concentration Camps, by Anne Applebaum, is published by Allen Lane, $59.95.

Probably the three worst camp complexes were the three built north of the Arctic circle: Vorkuta, Norilsk and Kolyma. The climate alone made life in these camps unbearable: the sun did not shine for six months of the year, winter lasted for 10 months, summer was made unpleasant by swarms of mosquitoes. Because of the climate, these camps also seemed to attract the harshest, and most corrupt, administrators, as well. Of the three, Kolyma was probably worst of all, simply because it was so far away from "civilisation". The camp complex was located in the far north-east of Siberia, in a region inaccessible except by boat from Vladivostok. To Muscovites and Leningraders, it seemed like another country.

Original Source for This Story Was Found on the Internet, July 2, 1998, at Sunday Times and is archived under the "fair use" provision of U.S.C. Title 17

Section 107 for scholarly, educational, and personal use by those previously

requesting such.

Christians Arrested by Jewish Bolsheviks Are Still Prisoners of Injustice

Stalin's Forgotten Prisoners...

Original Source for This Story Was Found on the Internet, July 2,

1998, at Sunday Times

and is archived under the "fair use" provision of U.S.C. Title 17

Section 107 for scholarly, educational, and personal use by those previously

requesting such.

THROUGHOUT his tortuous 10 years of hard labour in Stalin's gulag, Pavel Negretov dreamt of the new life that would begin on the day he finished his sentence for anti-communist activities. Still a young man, he imagined himself starting afresh in Moscow, far from the horrors he had endured.

That new life never came. More than half a century later, Negretov remains stranded in Vorkuta, in the Arctic Circle, where he was sent to work in barbaric conditions in the coalmines of Russia's far north. Now 75, he has yet to be granted the residence permit he needs to move with his wife to the Russian capital.

Negretov is not alone. Hundreds of former opponents of Stalin's dictatorship, including 250 in Vorkuta, have been left to their hard lives in remote regions to which they were exiled in the 1930s and 1940s. Most have struggled ever since to return to their home towns and villages. Thousands have died of old age without being allowed to resettle.

"There are queues of former political prisoners waiting to leave Vorkuta," said Yevgenia Khaidarova, of the local branch of Memorial, a human rights organisation that helps victims of Soviet repression. "The scene is the same all over Russia. These people are caught in limbo, living in a terrible vicious circle - they can't resettle without a propiska [residence permit], which they could get only if they had a flat in the city they wanted to go back to." Those dispatched to the gulag had their flats confiscated by the authorities. With their homes, they lost their right to live in the places where they had grown up with their families. If they were affluent, they could buy a privatized flat.

Deprived long ago of any opportunity to establish themselves, however, they are poor. If they moved without an official permit, they would have no legal right to work or to receive vital benefits, including healthcare.

Like the overwhelming majority of Russians, they depend on the state to provide them with homes. So they wait in the frozen Arctic, hoping forlornly that one day the state will find them a flat somewhere - anywhere - other than Vorkuta.

Isolated from the outside world by inhospitable tundra, 100 miles north of the Arctic Circle and more than 1,000 miles from Moscow, Vorkuta is a place where winter lasts for 10 months and the temperature falls regularly to -40C. It is completely dark for weeks on end. Like the other labour camps scattered across the northern wastes and christened the gulag archipelago by Alexander Solzhenitsyn, a camp survivor himself, Vorkuta was uninhabited until geologists found huge coal reserves beneath its frozen earth. Slave labour was the only way to develop the mineral wealth.

The first prisoners were sent to Vorkuta in 1931 on a journey that took six months and claimed thousands of lives. They were crammed first into cattle trains, then onto barges along several rivers and completed the last 50 miles on foot. Between 1934 and 1954, 2 million were sent away to toil in Vorkuta's 80 mines - petty criminals, political opponents of Stalin and the hapless, innocent victims of senseless purges, "guilty" of anything from simply being related to a foreigner to having turned up late for work.

"My first year and a half was the hardest," recalled Negretov, who arrived in Vorkuta at the height of winter after being arrested in Ukraine in 1946 for collaborating with an anti-communist group. "I thought I had landed in hell. "There were three shifts of eight hours. We were escorted at gunpoint in the snow from our barracks to the mines. It was always pitch-dark, with freezing temperatures, but the wind was the most terrible thing. I used to wonder why my parents had brought me into this world. I was skin and bones, and covered in ulcers."

The inmates slept in pairs to keep warm, using one jacket as a mattress on the floor and the other as a blanket.

"We kept our boots under our heads to stop other prisoners from stealing them, and pulled our trousers down over our feet to prevent frostbite," Negretov said. "Every morning an angry corporal would wake us up, shouting. That was the worst time - waking up to another day, exhausted."

Every day in Vorkuta, prisoners starved, froze to death, were executed by guards or were killed digging in the mines. Memorial, which was headed by Andrei Sakharov, the dissident nuclear physicist, until his death in 1989, has obtained access to archives in an attempt to calculate the toll. The initial estimate is half a million dead. Today, the graves are marked by numbered, nameless wooden crosses in seven cemeteries that surround a city of 180,000 people built on bones.

"I have been here 52 years, and I have dreamt all my life of living in a city like Moscow or St. Petersburg," said Negretov. "Our state has no conscience. It has forgotten about us and the Russian people as a whole. We have no democracy, only greed for more power. And who is Boris Yeltsin? A former Communist party boss. Power has not changed hands."

Since the advent of glasnost, the Russian government has rehabilitated most former zeks - as gulag inmates were known - formally recognizing them as innocent victims of repression and providing them with minimal compensation and the right to a proper pension. But it has done little to help them resettle.

Negretov fought until 1995 to be rehabilitated. He was awarded £700 compensation for the 10 years he sacrificed in the mines. All he really wants, however, is to move to any large Russian city. He was finally offered resettlement last month, but to the acrid smokestacks of Dzerzhinsk, the dangerously polluted centre of Russia's chemical industry.

Memorial has written several times to Yeltsin and the Russian parliament, urging them to help the last gulag survivors go home. But the Kremlin has other, more pressing matters to attend to.

Along with Vorkuta's ageing former prisoners, hundreds of unemployed young miners have joined the clamour to leave in search of a brighter future. They constitute a more menacing force for change. Since taking up the cause of the former inmates with the aid of the Solzhenitsyn Foundation, which is run by the writer's wife, Natalia, Memorial has managed to help several gulag victims resettle far from Vorkuta, but seldom to the cities of their choice. Some who were moved to rural backwaters without heating or hot water were so disappointed that they returned to Vorkuta.

Gulag survivors have received little support from ordinary Russians in their quest to return home. When Stalin's death in 1953 led to the release of millions of prisoners, even their families often refused to take them in, for fear of persecution by the KGB.

"The first thing I did when I was let out was to get on a train back to Moscow," said Lyubov Kalashnikova, who spent a decade in Vorkuta's camps. "I still had a brother and sister living there. "They hadn't seen me for 10 years but nobody dared welcome me home. They were too scared. Everyone was terrified of being associated with me." She was eventually forced to go back to Vorkuta. Decorated for bravery as a volunteer in the Soviet army during the second world war, Kalashnikova, now 78, was accused of treason in 1941 because she had survived a German ambush. Her superiors said she should have turned the gun on herself rather than risk capture. When she became a "free" woman, she made an annual, 46-hour journey by train to Moscow for 15 years in a vain attempt to plead for a residence permit. "I have tried to return to Moscow all my life," she said.

Kalashnikova, who can barely walk and lives with her disabled daughter in a tiny flat in Vorkuta, has never been given any hope of success. Instead, every year, she receives the letter Yeltsin sends to all veterans, congratulating them on the anniversary of the end of the war.

"I don't want to die here," said Kalashnikova, whose baby son died from diptheria in the camps at the age of two. "I hate this town. It is a symbol of death. I buried my life here, my destiny, my happiness. "My only wish is to return to Moscow, to die in my homeland. I have not lived here. I have simply existed. That has been the most painful thing - just seeing my life pass away, crossed off, erased without trace. Russia has forgotten about us."

Vorkuta & Pechora

Prisoners and slaves of the Vorkuta and Pechora camps who worked in temperature

below zero, coerced by the desperate instinct of survival ate their own

vomit and even flesh of killed fellow prisoners." Ethnic Cleansing

and Soviet Crimes Against Humanity by Altaullah Bogdan Kopanski.page 5

Which time was the worst? The worst era, unquestionably, was the war era. In the winter of 1942-43, about a quarter of Gulag prisoners died. The cause, quite simply, was the total disruption of the economy and of transport systems, which led to genuine starvation. Whole camps received no supplies whatsoever for weeks on end.

USSR database

That is an invaluable source of data on Russian (USSR) soldiers died or

disappeared during WW II compiled by Russian Defense Department. Search

by name works well. Also they show original documents as well. The original

documents are incredible! Some have photographs or fingerprints. The language

is Cyrillic, German and others possibly. The address is http://www.obd-memorial.ru/